Federal Flexibility for Care Delivery Innovation Should Outlast COVID-19 Emergency: The Case for Hospital-at-Home

In March 2020, as epidemiologists were predicting surging cases of COVID-19 illness that could overwhelm our critical care and acute care capacity, federal and state regulators responded swiftly. A host of regulatory barriers were removed to enable the delivery of care outside acute care hospital settings.

The medical groups and health systems who are members of CAPP leveraged new flexibilities to provide hospital level care in the home. In addition to relaxing many rules that inhibited wide use of telehealth services, rules governing what type or level of care could be provided and where it could be provided have also been relaxed. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) lent its support by issuing guidance for caring for patients with COVID-19 and recovering from COVID-19 at home.

Decentralization of care produces safer treatment for patients with and without COVID-19 illness by keeping them apart and protects care teams by preserving limited personal protective equipment and enabling the expansion of ICU-level capacity within hospitals.

“Hospital-at-home care will be an important option for otherwise stable patients with newly diagnosed SARS-CoV-2 infections and for early discharge of patients admitted to hospitals.”—New England Journal of Medicine

Many of the CAPP medical groups had already developed “hospital-at-home” care models. These models organize care to support patients in their homes or long-term care facilities using technology, teams, and tested criteria for eligible patients and conditions. Partnerships with Medicare Advantage plans enabled many of the medical groups, including Marshfield Clinic, Intermountain Health, Ochsner Health, and Geisinger Health to pilot hospital-level and post-acute services that rely on a mix of in-person home health care, telehealth, and remote monitoring. Other health systems, such as Northwell Health, honed their capabilities by participating in Medicare’s “independence-at-home” demonstration. Some medical groups partner with home health agencies, while others, such as Atrius Health, operate their own agency.

With Protocols in Place, Scaling Was Possible

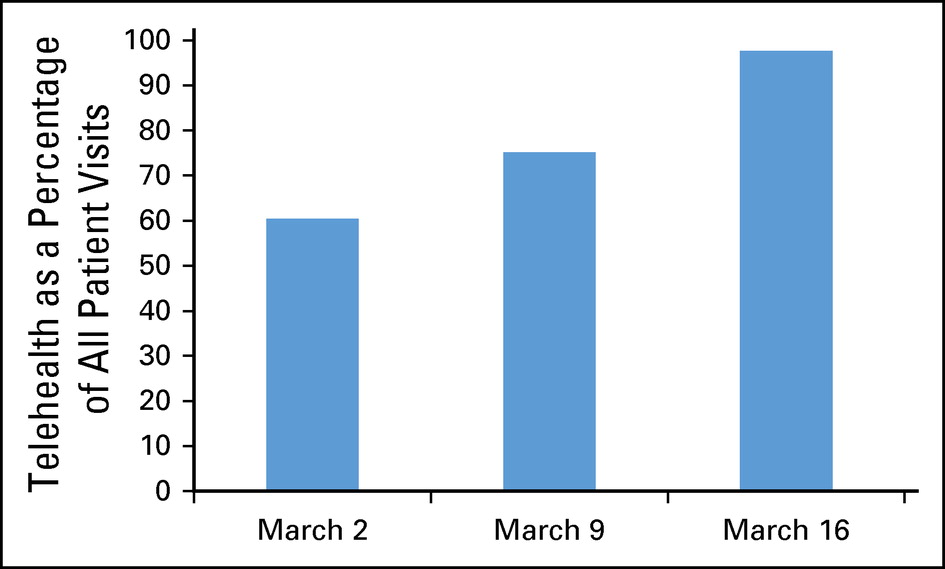

Integrated medical groups that already had experience developing protocols and delivering care via telehealth and other virtual care tools were able to scale their practice quickly. A few years ago, Permanente physicians developed, piloted, and evaluated small scale hospital-at-home programs that focused on patients with acute conditions, including congestive heart failure, pneumonia, cellulitis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Permanente Medical Group of Kaiser Permanente Northern California shared its progress in treating cancer patients using telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic. Virtual navigators provide coordination of tests, imaging, and virtual visits to minimize unavoidable in-person visits. A virtual triage service is available to identify patients’ needs, including individual and group support sessions, nutrition, and social work consultations.

COVID-19 challenged physicians and teams to deliver more care in the home virtually. For families, this model can seem daunting without good communication and preparation by the care team.

Post-Acute Options Are Limited

Patients recovering from COVID-19 illness must be discharged to conserve inpatient capacity, yet must also test negative for the virus and have someplace to go where they can be monitored and receive any additional rehabilitation or other services they may need to recover. For patients who have a home to return to, that is most often the best place to recover. For those who do not have a home to return to, hotels, nursing homes, and other settings like field hospitals have been used. However, high-risk patients make up the majority of patients in post-acute facilities, and infection controls are often weak in these settings. Also, there is concern that patients with COVID-19 who are cared for at home could infect family members. A range of alternative care settings are needed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Shantanu Nundy and Kavita Patel, writing in JAMA Health Forum, make the case for expanding hospital-at-home programs during the COVID-19 pandemic by waiving Medicare’s two-night minimum hospital stay rule and other barriers, while expanding the research base for hospital-at-home for specific conditions and patient criteria. One of the reasons CAPP medical groups have been early adopters of hospital-at-home models is that they care for a large number of Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage, where a waiver of the minimum two-night hospital stay already applies.

Almost all the regulatory and payment changes made by federal and state authorities during the COVID-19 emergency are temporary for the duration of the emergency period. Many of them should be made permanent to accelerate reforms and innovations in care delivery that make it more resilient in the event of disasters or emergencies. Of course, it is important to establish policies and criteria for patients, services, and clinicians who can receive and provide hospital-level care outside of the hospital, and particularly in the home, and to evaluate outcomes as more complex care is provided at home.