Why is Prevention Important?

What Can We Do About Medical Errors?

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) accomplished two main goals:

- to provide affordable healthcare insurance to more Americans, and

- to change the healthcare delivery system, improving the quality of care while controlling costs.

As of 2011, just prior to passage of the ACA:

So far, the ACA has managed to provide more health care coverage to Americans:

But considerable work still needs to be done to improve the cost and quality of the health care Americans receive:

Since the passage of the ACA, great strides have been made in improving insurance coverage nationwide, but more work must be done to improve the cost and quality of healthcare. This part of health reform requires that doctors and other medical professionals work together to improve the way that healthcare is delivered to patients.

This is what we at the Council of Accountable Physician Practices and our partners are striving to do.

OECD countries are those with above median total GDP and GDP per capita for at least one of the past ten years.

Health Reform FAQs

- Why is healthcare delivery system reform as proposed in the Affordable Care Act necessary?

- The various delivery-system reform provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (H.R.3590) and the Health Care Education and Reconciliation Act (H.R.4872) — together known as the Affordable Care Act (ACA) — strive to achieve the “Three Part Aim”: improving the experience of care for individuals, improving the health of populations, and lowering per capita costs. In order to achieve those goals, the existing payment models and health care delivery system need to be changed.

Despite general public perception, the healthcare system of the United States does not deliver the best care it can (see Health Care Facts on this website). Yet, it is the most expensive healthcare system in the world. The ACA aims to move the healthcare system away from its current episodic, fee-for-service payment approach and towards a coordinated model that is focused on delivering high-quality, low-cost care across the continuum of care. The fee-for-service method of paying for healthcare can create incentives for providers to deliver more care, but not necessarily better care. Developing a payment system that rewards quality outcomes and stewardship of healthcare resources is necessary for America to rein in its costs and improve the overall quality of the healthcare system.

In addition to changing the method through which providers are paid for health care, it is also necessary to reform the way in which that care is delivered, i.e., reworking the delivery system by creating high-performing organizations of physicians and hospitals that use systems of care and information technology to prevent illness, improve access to care, improve safety, and coordinate services—in other words, to become accountable for the quality and cost of American health care.

- What’s wrong with the way our healthcare system is currently structured?

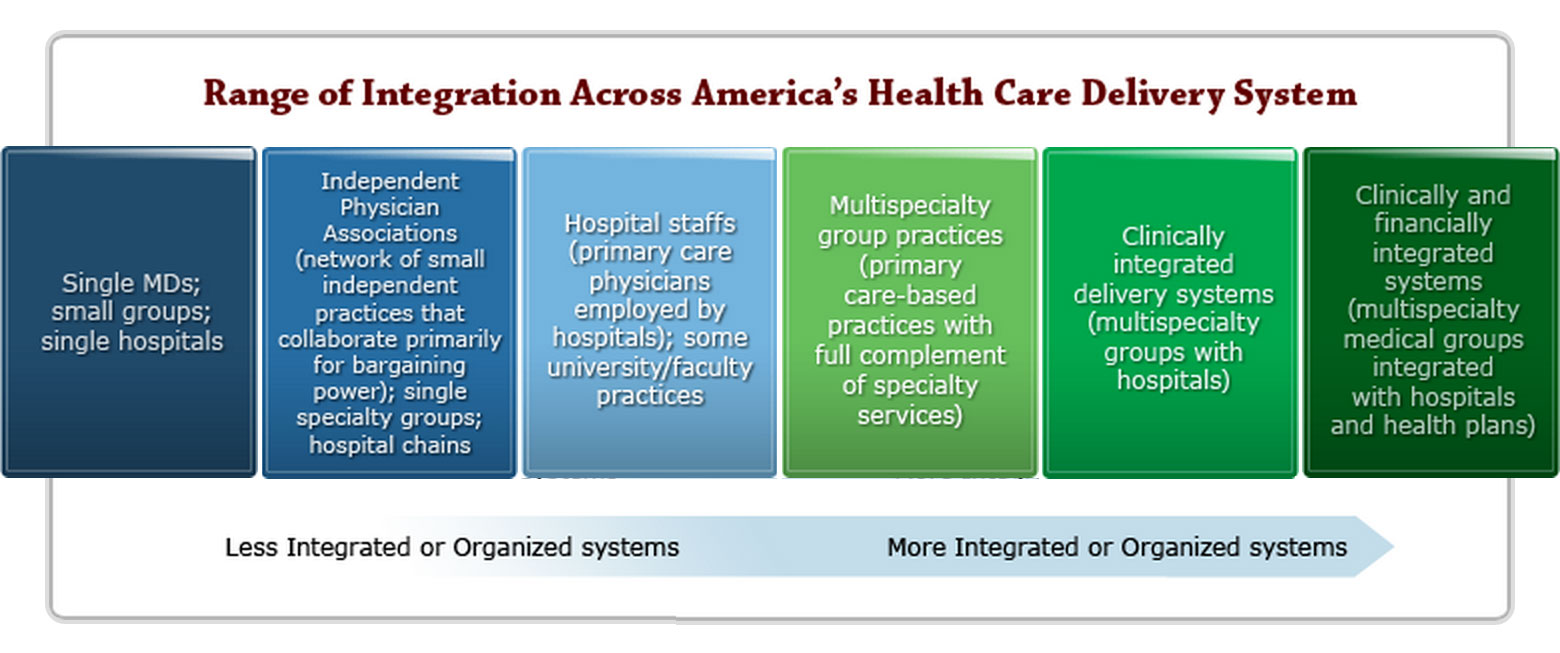

Not all health care is delivered the same way in the United States. In fact, there are several models of care delivery systems that range from practices that are not integrated to complete integration (see below).

Fragmentation of healthcare infographic: http://c0024345.cdn1.cloudfiles.rackspacecloud.com/LegislativeDownload.pdf

At one end of the spectrum, solo and/or small practice physicians work independently of each other and of other health care providers, such as hospitals, nursing facilities, etc. — not as one single system of care. As a result of this fragmentation, these healthcare providers can have difficulty sharing information and keeping track of a patient’s care and condition.

At the other end of the continuum, there are larger, more coordinated and organized healthcare systems that have hospitals, doctors, and sometimes even health plans that all work together.

The American delivery system’s current fragmentation is a significant contributor to the increasing costs of our health care and to the inconsistent quality of medical care our citizenry receives.

On the other hand, healthcare systems that provide care coordination have shown success in reducing waste, increasing communication between providers, and coordinating medical services, all of which saves money, enhances quality, and creates value.

Realizing that more organized systems of care produce better quality medical outcomes, The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services is testing new forms of care delivery modeled after these kinds of systems, such as Accountable Care Organizations.

- What is an Accountable Care Organization?

- An Accountable Care Organization (ACO) is a partnership of healthcare providers who choose to work together in a way that will improve the quality, coordination and efficiency of the care they deliver to a defined group of patients. The providers in this partnership can include primary care doctors, specialists, hospitals, therapists, and other medical professionals. The goal of forming these kinds of relationships is to better organize the way care is delivered by removing the fragmentation and silos that exist between care providers.

ACOs also measure and report on the quality of their medical care—this is what makes them “accountable.”

ACOs are now being formed around the country for people over 65 to meet the new care guidelines of Medicare, and for people who have insurance through their employers, like Blue Cross, United, Aetna, etc. ACOs are also being formed to serve Medicaid patients in order to improve the coordination of care.

- What’s the difference between an ACO and a CAPP medical group that considers itself an “accountable physician practice”?

- The concept of ACOs was actually built on research conducted with CAPP medical groups and others that believe that organized systems of health care are better able to measure and monitor the care they deliver so that care can be continually improving and costs can be controlled.

Many of the CAPP and AMGA medical groups have worked with Medicare and private insurers as ACOs. The difference is that CAPP groups have been providing care in an organized accountable way for decades. Our organizations have pioneered this kind of medical care. While we welcome the move towards more “system-ness” in healthcare and more accountability, we continue to watch and guide the current ACO movement to ensure that the evolution of the American healthcare system stays on a good course.

- Why are Accountable Care Organizations important to achieve improved cost and quality?

- The belief is that, if well conceived and implemented, ACOs can achieve both cost and quality improvements because the coordinated and collaborative nature of the delivery system itself is paid for and rewarded for its outcomes, not for its volume of services.

Therefore, the structure of an ACO becomes important: experts believe that ACOs must be physician-led, primary care-centered, and patient-focused systems of care. Currently, there are many health care systems of physicians and hospitals that function like ACOs, and the research conducted on these entities support the prevailing notion. By encouraging the evolution and growth of ACOs through payment incentives and a favorable regulatory climate, ACOs may be the most promising mechanism to control costs and improve quality and access in the American healthcare system.

The ACO concept is one that has been widely discussed among health researchers and pundits. According to the Commonwealth Fund, 54 percent of health care opinion leaders believe that ACOs are an effective model for moving the U.S. health care system toward population-based, accountable care. The Congressional Budget Office projects that the Shared Savings Program will save the Federal government $5 billion between 2010 and 2019.

Note that while the government focus on ACOs is within the context of Medicare, the concept applies to all patients covered by private-sector insurers that are also sponsoring such efforts. If ACO development can extend beyond the Medicare program, the advantages are clear: physicians and other providers will be able to interact with both public and private payers based upon consistent incentives and “rules of the game.” In addition, quality and care coordination will improve for all Americans, irrespective of age or payer.

- Is an ACO the same as an HMO?

- ACOs are not health insurance plans like HMOs and PPOs.

ACOs actually contract with health plans (and Medicare) by agreeing to measure and report on the quality of the health care delivered. There is a particular focus on preventive care, team coordination and continuity; these traits have proven it’s possible to improve patient health while reducing long-term costs. ACOs are rewarded financially when they improve the health of patients while containing expenditures.

The insurer-directed ACOs remind many of the HMO movement of the 1990s. Since that time, however, the term HMO has come to mean different things. Today, HMOs generally refer to: 1) Fully integrated delivery systems like Kaiser Permanente, where the insurer, physician groups, and hospitals are part of one integrated organization, and care is provided to only those who are insured by that organization; and 2) private health-plan products that call themselves HMOs, but are fundamentally only payment contracts with a network of mostly disaggregated physicians and hospitals.

In the former, care and cost can be managed much more effectively because clinical information and care processes are shared and supported by all providers. In the latter, care and cost are less easily managed because the providers are bound only by contractual agreements, not by care processes, shared incentives, or a common mission or shared values. Kaiser Permanente, an HMO, has for many decades delivered strong care coordination and integration of clinical services, care management, and clinical integration systems that many people are looking for in the ACO model. While some HMOs could meet the test of an ACO, not all of them have currently the capability.

- How can accountable care be useful to transform the U.S. health system?

- Changing the U.S. health care delivery system is no small task, but obviously a worthy one. The fact is that our current system is not providing better care for Americans even though we lead the world in healthcare spending. Our system is fragmented, providing care in silos where providers do not communicate well with one another.

This creates redundancy of medical services, increases the chances for medical errors, and no one is accountable for monitoring patients to ensure good health outcomes.

In addition, our system of paying for every service that is provided (the “fee-for-service” payment model) rewards providers for the volume of services but not for the quality.

Organized delivery systems like Accountable Care Organizations are centers for leadership and change. These doctors are practicing the way they believe medicine should be practiced—striving for the best outcomes, being strong stewards of healthcare resources and dollars, and providing patient-centered care.

This model is working and people are starting to take notice: the media, health insurance plans, medical students, policy makers, and most importantly, patients.

- What is the importance of linking of outcomes measures to payments?

- In a word, accountability.

For too long, the American healthcare system has not been effective in delivering quality care to all Americans or in managing our healthcare dollars. The healthcare costs for our nation are ever-increasing and our system is the most expensive in the world, yet measures of medical quality indicate that we are not living longer, or healthier, or receiving the best care we can for the dollars we are spending. And one reason why is that the current fragmented, volume-based, system is not accountable to payers or consumers and is unsustainable.

The Affordable Care Act recognizes the need for care coordination and accountability. In order to assure accountability, health outcomes and performance measures are needed to assess whether or not payers and consumers are getting value for their healthcare dollar.